The Cultural Cold War and Alien Abduction

Budd Hopkins, Abstract Expressionism, Hypnotic Regression, Screen Memories, American Exceptionalism, and Recurrent Problematic Patronage in the Arts and Sciences

(Note: This article began as a smaller section of a Cystic Detective Update but as often happens, I spent more time and effort on it than I anticipated. By the time it was completed, I figured it might be better suited as a free article.)

A tweet I saw recently brought my attention to a headache-inducing Washington Post op-ed from 2018 calling for the CIA to bring back the cultural Cold War.1 This refers to the Agency’s funding of the arts to stamp out the communist boogeyman which wound up blessing us with a hyper-individualist cultural product industry that often does not address the systemic class issues but tries to sidestep them altogether. An anticommunism by any means, even if it requires manufacturing a nominally superior culture. In Frances Stonor Saunders’ seminal book The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, it is revealed how these programs were also exported abroad, hoping to “inoculate the world against the contagion of Communism and (…) ease the passage of American foreign policy interests abroad.”2 It was a huge covert program and while its success or failure cannot be quantitatively accessed, it greatly expanded the soft power capabilities of the United States and was a uniquely suited propaganda mechanism.

As such, I have often wondered how ufological or broader paranormal research groups might fit into this picture, especially considering the cultural cachet of these topics. Perhaps without Saunders knowing she was doing so, the book includes an illuminating quote from one of ufology’s best loved (and hated) luminaries. In a chapter focused on Jackson Pollack’s appeal to American interests, a familiar voice offers some perspective:

“He was the great American painter,” said fellow artist Budd Hopkins. “If you conceive of such a person, first of all, he had to be a real American not a transplanted European. And he should have the big macho American virtues; he should be rough-and-tumble American—taciturn, ideally—and if he is a cowboy, so much the better. Certainly not an Easterner, not someone who went to Harvard. He shouldn’t be influenced by the Europeans so much as he should be influenced by our own—the Mexicans and American Indians and so on. He should come out of the native soil, not out of Picasso and Matisse. And he should be allowed the great American vice, the Hemingway vice, of being a drunk.”3

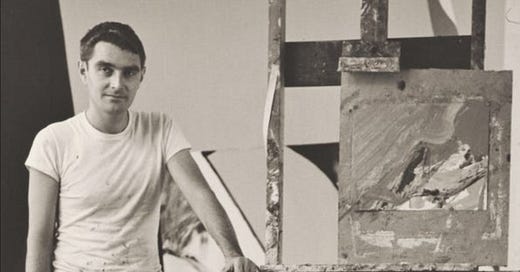

This lengthy quote comes from abduction researcher Budd Hopkins—also a generally well-regarded abstract artist—in a BBC documentary, co-produced by Saunders, about the art world’s CIA connections, Hidden Hands: A Different History of Modernism. While Hopkins, to my knowledge, never received any direct CIA funding for his art, this cultural seeding did not necessarily work in this way. He nevertheless benefited from the Agency’s promotion of abstract expressionism as a form of American cultural dominance, and several of his friends, such as Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, were more direct recipients of the CIA’s generosity.4 Some were more eager to please the CIA’s agenda, like the staunchly anti-communist Rothko, while others were less comfortable. de Kooning came to feel that the required “American-ness” was “a certain burden.”5 Hopkins’ feelings on the matter seem a little less certain, but his above quoted statements make it clear he had strong ideas about what made for a true American artist. Setting aside the fact that Hopkins’ native art movement was part of a great “ideological laundering” perpetuated by the CIA, I of course found myself wondering if this has any bearing on his abduction research.6

When watching the archival footage within last year’s Netflix documentary following Hopkins’ investigation of purported abductee Linda Napolitano, I was struck with how the support group functioned akin to a performance art collective. The performances, however, were traumatic recall brought about by hypnosis, like primal scream therapy with science fictional overtones. While I am not averse to anomalous experience, by now you should know I don’t hold a high opinion of hypnotists, especially those who you can approach and get your own stereotypical abduction story without fail. Nevertheless, Hopkins took his work seriously, and even though he was working backwards from a preconceived notion, in some ways his exploration into the abduction enigma was an artistic and associative process. His sensationalistic conclusions were likewise convincing enough for some investors. These include paranormal piggy bank Robert Bigelow, who financed a “roper Poll in which Hopkins, (David) Jacobs, and sociologist Ron Westrum incredibly concluded that about four million American had experienced UFO abductions—without ever even asking any of the survey participants.”7

Sometimes the art boosters and UFO enthusiasts intermixed, as in the case of the Rockefeller family, who had a “proliferation of links to the Agency” and dipped their toes in both the realm of modern art and ufology.8 These links extended to the Museum of Modern Art, started by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller with her son Nelson Rockefeller serving as the president for a good chunk of MoMA’s history. Rockefeller himself “had headed up the government’s wartime intelligence agency in Latin America” and was aware of the intelligence plots being conducted through American art. Saunders writes: “He received briefings on covert activities from Allen Dulles and Tom Braden, who later said ‘I assummed Nelson knew pretty much everything about what we were doing.’”9 The MoMA was specifically contracted by the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs—also under Nelson Rockefeller’s purview—to arrange traveling exhibitions of modern American artwork, again with the end goal of illustrating American cultural supremacy. Budd Hopkins, before being an artist of some renown in his own right, worked “a lowly job selling admission tickets, memberships, postcards, and so on,” at the Rockefeller’s MoMA.10 It is intriguing that he would eventually take up the mantle of abstract expressionism, the exact style of artwork most heavily promoted by the CIA and subsidized by the Rockefellers. But therein lies the insidiousness of this covert cultural formation: It is likely that he grew to appreciate the style of artwork himself and saw the money it drew in, not only from the Agency directly, but from the art world who was told (with substantial clandestine prodding and CIA-funded culture publications) that abstract expressionism was the premier form of American art.

In a strangely fortunate turn of events, Nelson’s younger brother, Laurance Rockefeller, was very active in the world of UFOs, the paranormal, and alien abduction. While this might imply that he was simply the more “woo woo” sibling, Laurance, like his brother, was a founding trustee of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, what Saunders calls:“New York think tank subcontracted by the government to study foreign affairs” which “presided over some of the most influential minds of the period as they thrashed out definitions of American foreign policy.”11 Again highlighting some considerable possibility for overlap, Hopkins, much as he received funding or cultural cachet from the Rockefellers and the MoMA, sought out alien abduction research money from Laurance Rockefeller. Hopkins notes that when he, John Mack, and David Jacobs approached Laurance for backing, he kept in mind a story from his friend and abstract artist Willem de Kooning. Nelson Rockefeller, a “major collector modern art,” bought one of de Kooning’s “abstractions” and he was “invited to a party at the Rockefeller’s splendid New York apartment.”12

While the funding never materialized for the alien abduction study, that Hopkins and his cohort were able to attend a meeting with Laurance Rockefeller in hopes of financial backing says a lot on its own, indicating who amongst the elite were most capable of putting money into the subject, perhaps even swaying the field to align with their own viewpoints. It is worth noting that John Mack, who held the most positive view of the abduction phenomena, did receive a grant from Rockefeller on his own.13 Even Hopkins figured that: “The Rockefellers were (…) ‘hopeful Baptists,’ and therefore Laurence would probably be more predisposed toward John Mack’s benign and optimistic view of the (angelic?) UFO occupants than he would be toward the more anguished view David and I shared.”14 Hopkins’ observations are a strong indication that the will of the benefactor is an easy way to tell where the science or the subculture is headed.

The original title of Saunders’ book was Who Paid the Piper?, a question that I think applies to both abstract expressionism and alien abduction research. Much as Hopkins had no qualms about his patrons and their motives in funding or promoting his art movement, he did not question the backers of his abduction research. To a certain extent, this is a case of Hopkins holding beliefs and values that are genuine, but still in line with specific hegemonic forces, whether the CIA or more singular groups of culture-shapers. There’s also, as always, a monetary incentive. Just as the Central Intelligence Agency was attempting to mold American culture through funding and promoting a certain subset of American artists, a group of patrons coming from a (less broad) world of defense contractors and government spooks funded and promoted his abduction researcher. Lucrative book contracts and fringe research studies were keeping him afloat.

But Hopkins also offered a particular vision of the abduction phenomena, and while he was not completely alone in this, he separated it entirely from the United States military despite their constant implication in the alleged incidents. From Martin Cannon’s The Controllers: A New Hypothesis of Alien Abduction:

In correspondence with me, a noted abduction researcher wrote of an instance in which an abductee recounted seeing a helicopter during his experience; as the abductee testimony progressed, the helicopter turned into a UFO. During one of the (quite few) regression sessions I attended, I heard an exactly similar narrative. Hopkins would argue that the helicopter was a "screen memory" hiding the awful reality of the UFO encounter. But does Occam's razor really cut that way? Shouldn't we also consider the possibility that the object in question really WAS a helicopter – which the abductee was instructed to recall as a UFO?15

I, for one, entirely agree with Cannon here. There is a tendency amongst UFO regression hypnotists to pick and choose which elements of the abduction are “real” and which are “screen memories”—and for the ones particularly interested in accessibility and funding, the U.S. military could never be seen as being complicit in the abduction events let alone ultimately responsible. That’s a no-go when the foremost researchers in the field come from the military or defense contracting—a quick way to getting pushed to the fringes of the fringe.

Much as in abstract expressionism, we are stuck in the land of internal worlds rising supreme over a material reality. Screen memories, psychoanalysis, and directly interrogating perceptions—all of these methods behave as a battering ram against any notion of witnesses being accurate without the assistance of someone to guide their eye. While I may be pushing the metaphor, it does not sound that distinct from abstract art being used to undermine the socialist realism of the Soviet Union in the cultural Cold War. While it could be often idealized—the CIA would be quick to remind you of this as well—Soviet art nevertheless attempted to evoke an ideal world that is more grounded, i.e. a reality in reach for the viewer. Abstract art requires no grounding, the observer can formulate their own internal reading of the piece and it is largely correct, until a certain hypnotizing art critic can convince you otherwise. “Because of hypnosis, Hopkins is able to disconnect abduction from any accompanying UFO sighting,” political science professor Jodi Dean writes. “His work begins with the ‘feelings’ someone has that ‘something’ might have happened ‘sometime’ or ‘somewhere.’ Under hypnosis, some of these feelings turn out to involve abduction by aliens.”16 Some of the simplest abstractions, certain themes, vague shapes, and emotions can all become abductions with the assistance of a semi-trained investigator. I don’t think Hopkins’ art was as distant from the abductees as might be assumed, although they served as a different type of canvas: A formless, moldable psychological landscape. One can see the utility of this kind of cultural formation, less reliant on objective reality and shaped by only a select few individuals who have been granted the credibility to do so. But again, I may be pushing the metaphor.

People are contradictory, however, much as in art and life. In a Washington Post article about the popularity of UFO books towards the end of the 80s, Hopkins was quoted as saying: “I can understand the rationale of a government cover-up. (…) The whole economy—stocks, bonds, mortgages, capital investment—is based on the idea things are gonna be pretty much the same.”17 A stereotypical proponent of the unfettered American way of life might see extraterrestrial contact as a threat to its continuation. Hopkins, however, was more blasé, stating that if the others arrived, he would “rather be in the liquor business than the real-estate business.”18 Given that he thought the visitors were on Earth regularly, maybe Hopkins did not hold the patriotic convictions promoted by the cultural Cold War—those types would want to shoot the “others” to oblivion or view them as biblically foretold.

Then again, maybe, just maybe, Hopkins was unknowingly promoting subcultural notions of alien abduction completely severed from a material environment—taking circumstances that could be addressed externally, transmuting them into something internal. Even amidst hypotheses about the alien lifeforms and their quests to create genetic hybrids with human women, there are less fantastic but no less real forces in the world that create psychological states that feel like human experimentation from a cold and calculated scientific class of higher beings. But it is often seen as more productive to assign those feelings to an alien other somewhere out there in the stars instead of biotech companies, the surveillance state, the historical covert medical testing done by the military, pick your poison really. These are all entities that combine to create a strain of paranoia that is warranted and fixable, and there is an understated usefulness in taking it away from those arenas and into a more amorphous and ambiguous realm. Throughout my time looking at alien abduction research—a phenomena that began with several cases where U.S. military involvement seems likely—I am driven more and more to a frightening thought: Like the cultural formation of abstract expressionism, the phenomenon has been signal boosted if only because it represents another option—one filled with trauma, repressed memories, and horrific medical abuses—that is still somehow more palatable than assigning blame to the humans within the American order who do the deeds that cause this cultural hurt.

Thank you for reading Getting Spooked. If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, consider becoming a regular subscriber to get posts sent to your inbox. Become a paid subscriber to read dozens of archived posts, listen to members-only podcast episodes, or ask questions to be answered in Q&As. It is the best way to directly support the continuation of this publication.

I also started a referral program that rewards archive access to those who share the newsletter with others, so be sure to tell any friends who might find this work interesting. The leaderboard tab is public if you want the bragging rights of your referral numbers.

Email me at gettingspooked@protonmail.com with any questions, comments, recommendations, leads, or paranormal stories. You can find me on Twitter at @TannerFBoyle1, on Bluesky at @tannerfboyle.bsky.social, or on Instagram at @gettingspooked. Until next time, stay spooked.

Bunch, Sonny. “The CIA funded a culture war against communism. It should do so again.” The Washington Post. 22 August 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20180831110645/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/act-four/wp/2018/08/22/the-cia-funded-a-culture-war-against-communism-it-should-do-so-again/?utm_term=.63653be1227d.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. New York: The New Press, 1999. Page 1.

Ibid., page 214.

Brown, Susan Rand. “Budd Hopkins retrospective comes ‘Full Circle.’” Provincetown Banner. 20 July 2017. https://www.wickedlocal.com/story/provincetown-banner/2017/07/20/budd-hopkins-retrospective-comes-x2018/4502122007/.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. New York: The New Press, 1999. Page 232.

Ibid., page 231.

Brewer, Jack. The Greys Have Been Framed: Exploitation in the UFO Community. Self-published, 2016. Page 75. https://www.amazon.com/Greys-Have-Been-Framed-Exploitation/dp/1519579616.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. New York: The New Press, 1999. Page 219.

Ibid.

Hopkins, Budd. Art, Life and UFOs: A Memoir. San Antonio: Anomalist Books, 2009. Page 91.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. New York: The New Press, 1999. Page 219.

Hopkins, Budd. Art, Life and UFOs: A Memoir. San Antonio: Anomalist Books, 2009. Page 392.

Conroy, Ed. “Journalist who helped break Pentagon UFO story writes biography of John E. Mack, Harvard psychiatrist who studied alien encounters.” San Antonio Express-News. 7 July 2021. https://www.expressnews.com/entertainment/arts-culture/article/Journalist-who-helped-break-Pentagon-UFO-story-16298956.php.

Hopkins, Budd. Art, Life and UFOs: A Memoir. San Antonio: Anomalist Books, 2009. Page 394.

Cannon, Martin. The Controllers: A New Hypothesis of Alien Abduction. Self-published monograph, 1992. Page 23. Reprinted here: https://ia801701.us.archive.org/19/items/pdf_martincannon_thecontrollers/Martin%20Cannon%20-%20The%20Controllers.pdf.

Dean, Jodi. Aliens in America: Conspiracy Cultures from Outerspace to Cyberspace. New York: Cornell University Press, 1998. Page 51.

Suplee, Curt. “Take Me to Your Reader!: Accounts of UFOs Invade the Best-Seller Lists.” Washington Post. 9 March 1987. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP91-00901R000500180001-6.pdf.

Ibid.

I always tend to think about CIA involvement in abstract expressionism as similar structures that propped up artists throughout history: Churches (and royalty lol) had the money, so Michelangelo painted angels. Simply, the CIA was the new church. Artists will pretty much go where the money is for obvious reasons--some more willing than others lol. To my mind, that doesn't really have a totalizing impact what comes next. You don't have to believe in god to enjoy The Creation of Adam and what the artist was doing with the clay provided, and you don't have to believe in the cult of American individualism to enjoy an Untitled #4. Just my take.

EDIT: Also, loved this article! Forgot to mention that real quick lol

This is one of those posts that reminds me why I keep coming back to Getting Spooked. This is a fresh take, an important take, and a plausible take. Quite a rare trifecta of achievement in ufological circles these days.

I too watched the Netflix docu on Napolitano and Hopkins and came to similar conclusions, btw.