(Note: After a delightful holiday break wherein I became a happily married man, I thought it might be a good time to release another piece from the Getting Spooked vault. This time, inspired by a cross-country Christmas road trip, I revisit an essay I wrote in 2019 about the Kansas historical marker program and what it says about the state itself. This article feels especially relevant with the mainstreaming of denial with regard to the mass graves at Canadian residential schools by The Atlantic—a frustrating development to say the least. I am something of a historical completionist and our current era, within and outside of the paranormal, seems averse to maintaining historical consistency. I have tried to amend a few portions of the essay, but do note that the markers may have changed in the five years after this article was composed. True to the spirit of this newsletter, there are also some more spooky notions explored throughout our journey across the state, such as a portal to hell and the less ethereal phantoms that haunt the plains. Hope you enjoy.)

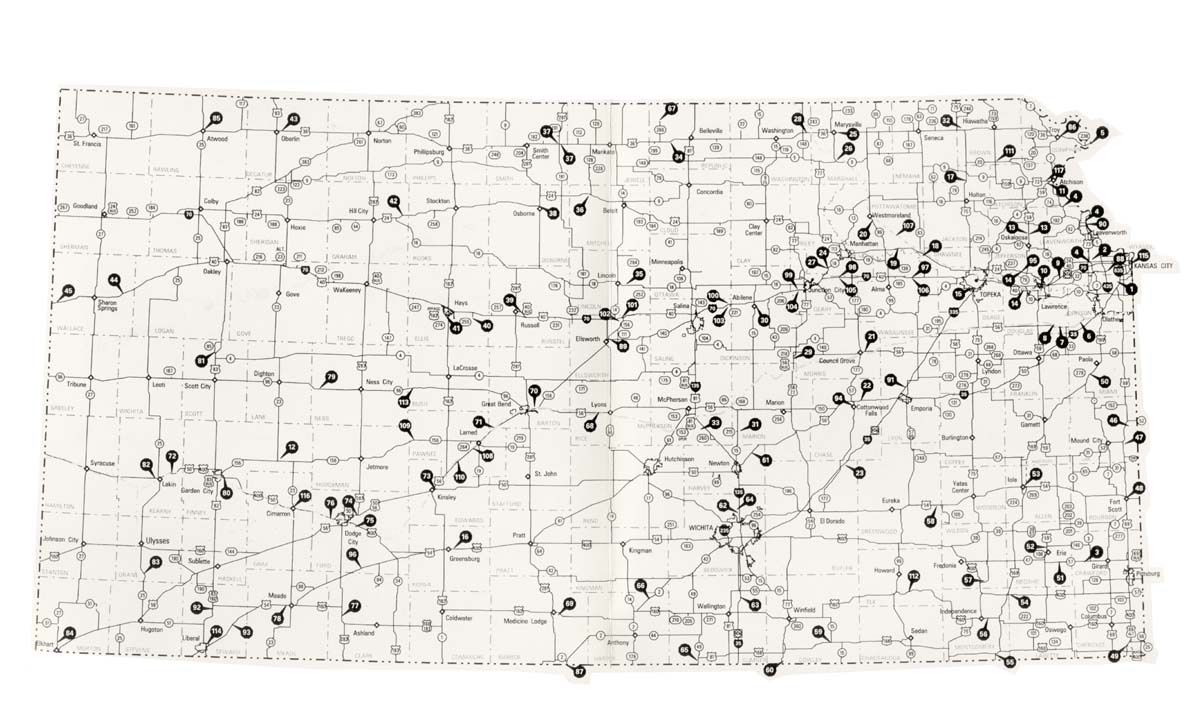

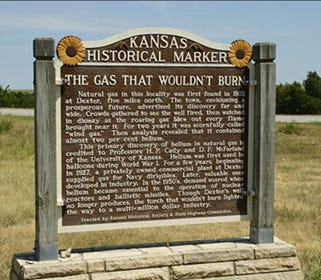

Natural gas in this locality was first found in 1903 at Dexter, five miles north. The town, envisioning a prosperous future, advertised its discovery far and wide. Crowds gathered to see the well fired, then watched in dismay as the roaring gas blew out every flame brought near it. For two years it was scornfully called "wind gas". Then analysis revealed that it contained almost two per cent helium.

This primary discovery of helium in natural gas is credited to Professors H. P. Cady and D. F. McFarland of the University of Kansas. Helium was first used in balloons during World War I. For a few years, beginning in 1927, a privately owned commercial plant at Dexter supplied gas for Navy dirigibles. Later valuable uses developed in industry. In the 1950's, demand soared when helium became essential to the operation of nuclear reactors and ballistic missiles. Though Dexter's well no longer produces, the torch that wouldn't burn lighted the way to a multi-million dollar industry.

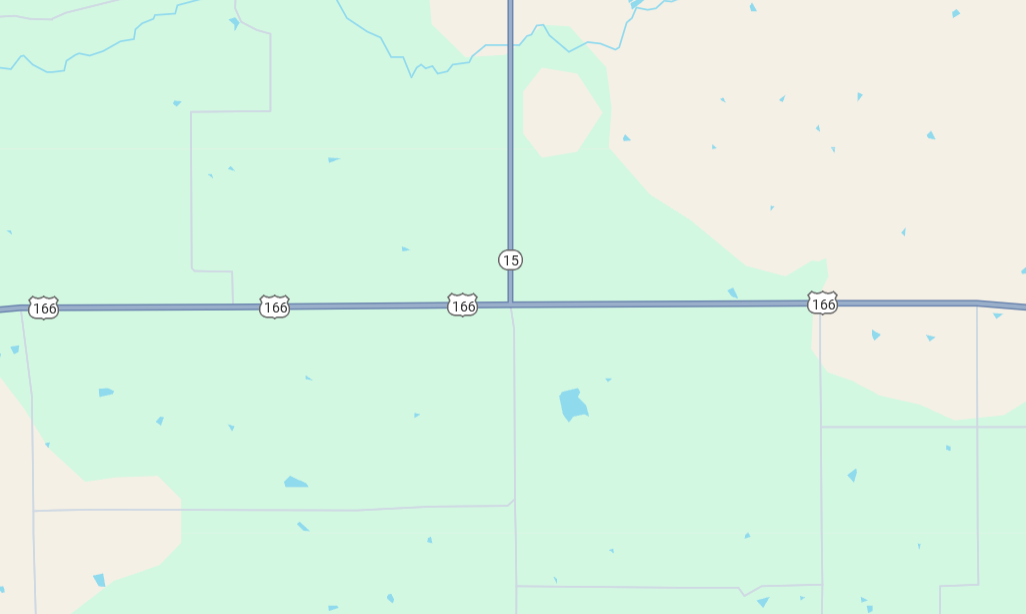

US-166, Cowley County

Roadside turnout, 12 miles west of Cedar Vale at K-15 junction

37.110601,-96.6436061

This is the text of the first historical marker I encountered in Kansas. The marker is innocuous, almost comical, and gives character to a largely unremarkable area of the state. To see the marker, you must pull off a state highway, US-166, at a side road that seems to exist solely for emergencies—sleepy truckers and possibly the carsick. Even within the county where I grew up, I hardly knew anyone apart from history teachers in my schools who knew about the historical marker’s existence. This marker, like most if not all the others in Kansas, recalls Marc Augé’s concept of “non-place”: “A space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity.”2 Augé relates this concept specifically to places of transit, using an airport as a prominent example of a non-place. Historical markers in general bear the hallmarks of Augé’s definition, being spaces that “are listed, classified, promoted to the status of ‘places of memory,’ and ascribed to a specific position.”3

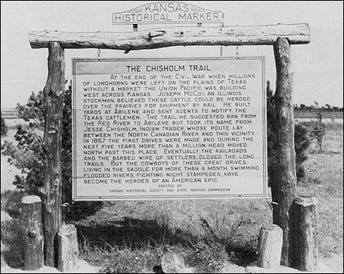

At times, this specific position can be eerie, as is the case with Marker #54 which is located amongst the “Bender Mounds” where the murderous Bender Clan buried the bodies of countless travelers—exact number and locations of the bodies unknown. Other times, the location of the markers is vaguer and clearly guided by their proximity to major thoroughfares. Marker #97, for instance, is about the cattle grazing potential in the area because of the bluestem grasses that grow throughout a large portion of the state. The marker, however, is simply and conveniently located along Interstate 70, likely the most well-trafficked highway in the state. It is also from Marker #97 that the first instance of a “structuring absence” makes an appearance, or perhaps its lack of an appearance. “For thousands of years prior to (cattle), the great bison herds roamed these acres,” the marker reads. “Their grazing and migration, along with periodic prairie fires shaped the ecology of the region. Eventually hunters drove the bison nearly to extinction.”4 What is the notable “absence” in this brief snippet of text? Unsaid is the fact that “both civil and military officials concerned with the Indian problem applauded the slaughter” of the buffalo, “for they correctly perceived it a crucial factor that would force the Indian onto the reservation.”5 This absence is also prevalent in Marker #80, “American Indians and the Buffalo”. This marker conflictingly includes a quote from Satanta, a Kiowa chief, that mentions how soldiers were shooting the buffalo but ignores the motivations beyond the economic demand for buffalo hides in the east. The marker is sure to mention the efforts of a white former buffalo hunter who raised buffalo in captivity, helping to save it from extinction, but again evades the motives behind the buffalo’s close call with extinction in the first place. As will be explored further in this piece, while Kansas’ historical markers attempt to historicize a specific location and write a very particular history of Kansas, oftentimes the markers will intentionally skirt around some of the more unsavory facts of Kansas’ history in order to give an appealing picture of the state to motorized tourists.

Attempts to quash any notions of dark histories from monuments and markers has been a consistent trend. A recent movement in the state of Texas aims to make history known through markers, dredging up memories of lynched Latin Americans and other mistreatments that the state would likely rather forget about: “Mobs hanged, whipped or shot Mexicans, many of whom were United States citizens, sometimes drawing crowds in the thousands.”6 Pushes by activists to commemorate these injustices have resulted in a historical marker placed alongside a Texas highway near the site of the 1918 Porvenir Massacre. This marker has proven to be contentious, however, with even the chairwoman of the historical commission being opposed to its placement. She “cited concerns that it was being used by ‘militant Hispanics’ looking for reparations” although the families seem to simply want the marker kept in place.7 Kansas historical markers illustrate a similar resistance to acknowledge negative histories of the state, although it does so through subtle absences in the texts as opposed to outright disregard of history. These absences appear insidious at times, although the Kansas Historical Society seems more inclined to fixing the language of the markers—as illustrated by their contact with the various Native American tribes who are mentioned in the texts in order to approve or disapprove of the wording.

Head of the Department of Geography at the University of Tennessee, Derek H. Alderman writes that “memorials, monuments, street signs, historical markers, statuary, preserved sites, and place-based festivals, performances, and re-enactments give the past a tangibility and familiarity—making the history they commemorate appear to be part of the natural order of things and facilitating a shared sense of place and time,” but notes that these objects have a “normative power.”8 Indeed, the Kansas historical markers tend to perpetuate a primarily positive image of the state and does not seem to have much criticism directed towards them, especially when compared to the marker for the Porvenir Massacre. The “normative power” of Kansas historical markers may be more prominent and less challenged simply because of the physical absence of Native Americans in the state after centuries of displacement and mistreatment.

One might note from these images that to read the text, a driver would have to stop—the markers cannot be easily read while continuing down the road. Furthermore, small brown signs alert drivers to upcoming turnoffs to view the historical markers, typically pointing to which side of the road the marker will be on. In the Kansas Historical Society’s original explanation of the goals of the historical markers, they make clear how intertwined the markers are with the recent development of automobility:

Until recent years it was the practice to erect historical markers on the sites where the events occurred. Frequently these places were inaccessible and usually the history consisted of a few words on a plaque or monument. It was assumed that only those already familiar with the facts would be interested. Today, however, with thousands of tourists on the highways, history is being marked where those who ride may read. Inscriptions on roadside markers often tell of events that happened miles away, and the history of a region may be condensed in one text.9

Indeed, the initial project has consistently been a joint venture between the Kansas Historical Society and the Kansas Department of Transportation; one key feature in the selection of topics was whether “KDOT could secure rights of way” for the locations at hand.10 Having a space so intimately tied to transit and mobility immediately resembles Marc Augé’s “non-places,” where the “user (…) is in contractual relations with it (or with the powers that govern it). He is reminded, when necessary, that the contract exists.”11 The roadways upon which historical markers are placed are consistently governed by state troopers, tolls, KDOT officials, and other entities, all connected to the state itself. Indeed, historical markers seem to be one of the “codified ideograms” we encounter in non-places, specifically “the ones we inhabit when we are driving down the motorway.”12 The historical markers come from a time in which the very notion of automobility across the nation was new, a sign of bustling modernity and the greatness of the succeeding country. Cultural studies scholar Michael W. Pesses notes that “as roads improved, so too did their purpose,” but that it brought up questions of what these roads were for: “Were roads to get from point A to point B? Or were they connected to the history of America itself? Many travelers viewed the landscape with awe and felt that the forested roadside was crucial to preserving the beauty of the country.”13 The role of the Kansas Department of Transportation in the placement of the historical markers implies that roads were indeed connected to the history of America, or at least to the history of Kansas. A so-called flyover state, many dread the prospect of driving through Kansas, a Midwest no man’s land that can get especially monotonous in the sparsely populated portions. The historical markers serve the dual purpose of being a tourism draw, a patriotic look at the landscape and history of the newly traversable nation, and an opportunity to showcase Kansas’ uniqueness within the Union.

Augé writes, “there is no room there for history” in a non-place “unless it has been transformed into an element of spectacle.”14 In this sense, the markers may be successful in elevating themselves from ahistorical non-places along nameless highways to quiet spectacles of Kansas history. They are unsuccessful, however, in giving the full picture of the state, perhaps being too quiet of a spectacle to be anything more than innocuous blocks of text alongside the spiderweb of roads that weave throughout Kansas. Indeed, the overall impression left by the historical markers is a largely positive one, reminiscent of the “success story” of Kansas portrayed in other congratulatory histories:

Perhaps no other commonwealth admitted into the Union during the last half of the last century has a greater historical impact than Kansas. Born in the storm and stress period of national political controversy, cradled in the tumult of the civil war, and reared to full statehood in an era unparalleled in the arts of peace, the life of Kansas has been one of intense activity.15

The historical markers also present Kansas largely as a state of great interest and promote the idea that its history is one of peace and innovation. They do so while ignoring the fact that although Kansas was early in its life a progressive state, an abolitionist and even socialist stronghold, its history is pockmarked by various instances of federal and colonial abuse that have left lasting impressions, in some cases quite literally shaping its borders.

Keeping in mind the physical connection these markers have to the concept of automobility, it is worth exploring how these brief texts attempt to portray and historicize the spaces in which they are placed. Many of these markers contain what Richard Dyer calls “structuring absences”: “An issue, or even a set of facts or an argument, that a text cannot ignore, but which it deliberately skirts around or otherwise avoids, thus creating the biggest ‘holes’ in the text, fatally, revealingly misshaping the organic whole assembled with such craft.”16 As Dyer says, the concept of the structuring absence “is also much open to abuse,” and it must be noted that some markers possibly suffer from spatial limitations—there is simply not enough space for the text necessary to give a complete picture of the regional history. However, subsequent rewrites of the markers in the 2010s indicate that these structural absences can be amended, which may serve as retroactive proof of the existence of an absence. These strong amendments to a few markers will serve as examples as to how the markers could be fixed, as well as indicating where the common structural voids appear in other markers about similar subjects—the markers without the detail of the amended examples feel noticeably as if they are lacking important details to neutralize themselves from questions of colonial authority. The second closest marker to my hometown was an immediate indication of this problem.

The Cherokee Outlet or Strip south of here was opened to a land rush in 1893. This tract of land was 60 miles wide and stretched along the Kansas-Oklahoma border. Due to a surveying error, a two-mile strip lay north of the Kansas border. The land had been the property of the Cherokees since 1836. As a result of the Cherokee Nation’s support of the Confederacy during the Civil War, the Cherokees were persuaded by Congress to eventually cede more than 8 million acres to the U.S. government for about $1 an acre, making the Cherokee Strip available to settlers.

Every eligible settler who could stake a claim would receive a quarter section or a town lot. Finally on September 16, 1893, more than 100,000 people lined the border awaiting the pistol shots that began the nation’s last great land rush. Competitors walked, rode bicycles and horses, and drove cabs, covered wagons, and buggies. By nightfall papers had been filed on dozens of new town sites, homesteads, and ranches.

Note: This sign was replaced in 2012.

US-77, Cowley County

Roadside turnout, south of Arkansas City at 312th Road

37.027112, -97.04812917

Contrary to the innocuous marker about the discovery of helium, the Cherokee Strip marker does not seem so neutral—regardless of its attempts to be so. While the text implies that the Cherokee Nation was being reprimanded for supporting the Confederacy, (and this no doubt played at least some role,) the reasons wound up being primarily those of economic benefit for settlers and the US government:

The Cherokees protested strongly, as they had earlier rejected the cattlemen's offer of $3.00 per acre, but protests were in vain. In February 1890 Pres. Benjamin Harrison forbade all grazing in the Outlet after October, effectively eliminating tribal profits from leases. Even though the army never managed to remove all ranching from the area, because of manpower shortages and other problems, the Cherokees agreed to sell the following year at a price ranging from $1.40 to $2.50 per acre.18

As with the motivations behind the slaughter of the buffalo, colonial forces made every move possible to push Native Americans off their land or eradicate them outright. Several of the settlements in this area were territories set up by survivors of the Trail of Tears and the support of the Confederacy was motivated by promises of sovereignty over their lands—a sovereignty that likely would not have been recognized by the Union whether the Cherokees sided with the Confederates or not. The marker clearly sidesteps the questionable nature of the US claiming this land, reinforcing the idea that the colonial forces deserved it as reparations for the Civil War. Although hard to quantify, it is doubtful that Confederate support offered by the Cherokees outweighed the decades of colonial abuse against Native American sovereignty that preceded it.

Further structural absences exist in the historical marker outlining Spanish conquistador Coronado’s search for gold in the state: “Coronado's objective was the land of Quivira, described to the Spaniards as a fabulously wealthy kingdom where gold was commonplace. In June the expedition entered the Arkansas River to what is now Rice and McPherson counties. The Spaniards found no gold, only the grass lodges of the Quiviran Indians, and the guide who misled Coronado was killed.”19 This marker does not mention the reasons why the guide (known by the Spanish expedition members as “the Turk”) misled them, and the absence leads one to believe that he intentionally and devilishly sent Coronado’s party astray and that Coronado was perhaps justified in strangling the man for his trickery. In fact, the factors surrounding the Turk’s motivations have been subject to intense debate among historians. Even Blackmar, in his rather dated language, outlines possible reasons why this is not the case:

In trying to trace these early dealings of the Europeans with the American aborigines, we must never forget how much may be explained by the possibilities of misrepresentation on the part of the white men, who so often heard of what they wished to find, and who learned, very gradually and in the end very imperfectly, to understand only a few of their native languages and dialects. (…) Much of what the Turk said was very likely true the first time he said it, although the memories of home were heightened, no doubt, by absence and distance.20

The fate of “the Turk” as portrayed in the historical marker is not the full story nor does it get at the brutality of colonial conquest in the Americas as the early colonizers searched for bullion. Yet, as shown by the following marker, the historical markers have no issue portraying the brutality of Native Americans—even if the brutality was in retaliation for other atrocities.21

In 1874 twenty-seven persons were murdered by Indians on the western frontier of Kansas. Several times during the summer, warriors broke away from the restraint of their reservation in Indian Territory (present Oklahoma) and moved north killing and plundering. On August 24, Chief Medicine Water and a band of twenty-five Cheyenne ambushed six men of a surveying company eleven miles southwest of here. After a running fight of three miles the oxen drawing the surveyors' wagon were shot. All the men were killed and three were scalped. Two days later their bodies were found by other members of the party and were buried temporarily in a common grave near a solitary cottonwood five miles south of this marker. For many years the "Lone Tree" which gave it name to this massacre was a famous prairie landmark.

US-54, Meade County

Roadside turnout, 1 mile west of Meade

37.285341,-100.36772922

The marker about the Lone Tree Incident is perhaps the most egregious example of misrepresenting Native Americans, this time resorting to characterizing them as violent savages. Though their motives may not have been enough to justify killing the land surveyors, the marker does not mention any sense of a motive, a motive that can be stated in one sentence and do some work in quelling notions of Native Americans as savages: “The Cheyennes had been angered by an order which called out 300 soldiers from Fort Dodge to drive the Cheyennes back to their reservation.”23 This addition would easily contextualize the incident without resorting to mentioning only the barbaric killing and scalping seemingly without provocation. The wife of Chief Medicine Water, a Cheyenne Indian named Mochi, was present at both the Lone Tree Incident and the earlier Sand Creek Massacre, in which an estimated 70-500 of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes—greatly outnumbered by colonial forces—were murdered, including women and children. Without these key details, the Lone Tree Incident seems entirely unprovoked, but the event was more likely to be a violent reaction after decades of being subjugated to colonial forces. The justification can be debated, but the event is not the clear example of malevolent Indian barbarism that the marker seems to imply through contextual absences.

In addition to the mistreatment of Native Americans in the area, other groups of people who were ousted from Kansas and nearby states are described with similar structuring absences. Marker #117 is situated in an area that served as a waypoint when Mormons immigrating from an unwelcoming Jackson County, MO trekked westward: “Near here, located in a grove of young hickory trees, was an important rallying point in 1855 and 1856 for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon), then emigrating to the Rocky Mountains.”24 This marker does not mention the Mormons’ reasons for immigration which was, like the Native Americans, a forced or instigated migration after numerous violent incidents between the Mormons and groups of inhospitable Missourians and Illinoisans.

Marker #112, which tells the history of the early proponent of equal education for African Americans, Prudence Crandall, notes how “over a hundred years later, legal arguments used by her 1834 trial attorneys were submitted to the Supreme Court during their consideration of the historic civil rights case of Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education.”25 Yet the there is no marker specifically for Brown vs. BOE, a landmark case in the national battle for civil rights. The court case was started by a Topeka, KS school refusing to enroll African American student Linda Brown at the school closest to her, instead opting to force her to go to the all-black school farther away. The very absence of this other marker may indicate a lack of completeness in the historical markers catalogue. However, the answer could simply be that the historical markers program saw no need to create a marker when there is a National Historic Site for the court case.26 Regardless, if one were to view the historical markers from the official program in isolation, there is a distinct absence: the term “segregation” never makes an appearance on a single marker. The program includes numerous markers about Kansas’ earliest history which is marked by progressivism, abolitionism, and racial integration, but do not have markers that depict Kansas’ eventual failings as a state, falling into racist statewide policies that continue to have some effect on the state to this day. The pronounced shift from being what would be considered a blue state in the 1800s to the current day state of deep red is not—and perhaps cannot be—reflected in the historical markers. The normative power of the historical markers rears its ugly head once again, but there are cracks in its veneer that can be utilized to achieve a history free of structural absences.

~

The tiny town of Stull, Kansas is one of the best examples of a Kansan landmark that attempts to rid itself of a history of incorrect associations. Supposedly one of the alleged seven gateways to Hell, the town itself is sparsely populated, and the local cemetery makes up most of the main strip. This cemetery is shockingly said to by populated by covens of witches and the Devil himself. An article published in the University of Kansas newspaper propagated several improbable myths about the town. Purportedly, the Devil appears in the cemetery every Halloween and Spring Equinox, a lonesome grave is the resting place of a child of the Devil and a witch, the old church on the cemetery grounds glows an eerie red at night, and despite having no roof, the interior of this same church is said to remain dry even if it is raining outside.27 The residents are, perhaps understandably, not happy about this. The myth has been circulated in various forms of media since the article was published and it has become a mecca for KU students looking to scare their socks off. The locals do not own this role. Rather than turn the town into a “haunted” tourist attraction as many have done with other places of great tragedy such as hospitals and battlefields, residents of Stull instead opt to fence off the grounds, hire a security force, and heavily fine anyone brave enough to enter. “Descendants of the resilient and quite religious German families who were the original settlers of Stull,” the townsfolk want nothing to do with these urban legends, finding them sacrilegious, offensive, and not reflective of the actual history of the town. “Disseminators” of the legend are frowned upon—even worse if they show up in town.28 Although the cemetery is now practically blocked from view by fencing and the church has been weathered down to just its foundations, legends persist. However, visits to Stull declined at the turn of the century. Lisa Hefner Heitz, who chronicled Kansas folklore in her book Haunted Kansas, notes: “The legend of Stull can definitely be seen as a cautionary (tale), an example of a legend that grows out of control and threatens elements of the very community that has produced it or maintained the landscape that has drawn it.”29

I relay this tale to illustrate how the power dynamics in Kansas function. The Native American, African American, and even Mormon communities in Kansas are all small minorities compared to the sizeable white, traditional protestant majority. Even the tiny community of Stull, which is made up almost entirely of this white majority, can police the way inaccuracies of their history are promulgated. Stull is a “non-place” that attempts to grasp tightly to its history, but the history that truly defines the area is that of spectacle—an urban legend that it cannot shake itself from. This is history that can be combatted, and the residents try their best to do so often to no avail. It is for this very reason that structuring absences can be an insidious force within historical markers. The history is not incorrect on historical markers as it is in the case of Stull, but the information, absences intact, proliferate through the state, and enter the knowledge of every resident. Kansas tales of unprovoked Native American barbarism circulate as freely as that of demonic churches. The markers have the ability to turn the history of places into legends of colonial superiority, buffing out every small blemish in the historical record to illustrate the unbridled greatness of the state. Whereas the devil is not in the details of the actual history of Stull, the devil of colonial abuses lurks in the details of Kansas history, often relegated to existing within structural absences, making them more devilish and difficult to track down or refute.

There are facets of Kansas history that the state can be proud of. Its earliest history is forever represented as battle between abolitionists and pro-slavery settlers who tried to sway the territory one way or the other. The state motto “Ad astra per aspera” or “To the stars through difficulties” reflects this struggle for a higher ideal—an ideal which Kansas seemed to achieve in several ways during this early history. It eventually entered the Union as a free state despite constant raids from neighboring pro-slavery states who attempted to sway the voting their way. The state was the home of radical abolitionist John Brown, the location of numerous raids by guerilla Confederate forces from Missouri, and—early in the 20th century—a nexus for progressive reform (a fact that now seems almost unbelievable). Historical markers are in place for many of the locations that, to the Kansas Historical Society, best represent these events and movements. The “Exoduster” city of Nicodemus, an anomaly of “racial harmony” in “the midst of a national surge of violent racism” in the post-Reconstruction era30, receives the following marker:

Nicodemus, established in 1877, was one of several African American settlements in Kansas. The 350 settlers came from Kentucky to escape the problems of the oppression of the “Jim Crow” South. Residents established a newspaper, a bank, hotels, schools, churches, and other businesses. They enjoyed much success despite the hardships and challenges of late 19th century High Plains settlement— wind, drought, swarming insects, and more.

The town grew rapidly through the 1880s and many prospered. But when Nicodemus failed to secure the railroad, growth slowed and the population began to dwindle after World War I.

Edward P. McCabe, who joined the colony in 1878, served two terms as state auditor, 1883-1887, the first African American elected to a statewide office in Kansas.

A symbol of the African American experience in the West, Nicodemus operates today as a unit of the National Park Service.

Note: This sign was replaced in 2011-2012.

US-24, Graham County

Roadside turnout, Nicodemus

39.394105,-99.61547131

While there is possibly a structuring absence in this marker as it does not explain why the town failed to secure the railroad—it is possible that it has to do with the deliberate removal of African-Americans from economic opportunities or it could be for more innocuous reasons—the very fact that such a refuge for Blacks evading the Reconstruction south existed in Kansas is an admirable feature of the state’s history.32 These features can be celebrated, but this does not mean the negative aspects of Kansas history should be ignored. The primary people interested in historical markers (history buffs, assumedly) are likely looking for an accurate and complete history of the point of interest, not self-congratulatory text.

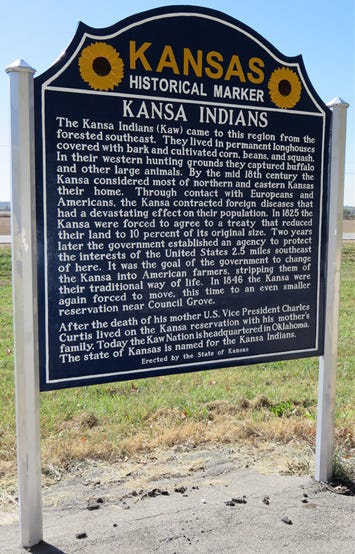

Likewise, the historical markers program is an understated yet immensely interesting tourism draw for the few who gravitate to them—as one drives across the state, the little markers serve as brief respites from automotive monotony and attempt to earnestly historicize the regions in which they are placed. The Kansas Historical Society has also been seemingly active in trying to make the markers have more inclusive language, and they have made strides to change the language of the markers whenever Native American tribes alert them to possible texts that were “inappropriately or inaccurately worded.”33 A document made available to me through the KHS had comprehensive notes regarding responses from various Native American leaders, one for each of the ten Nations depicted or referenced in the markers, about the texts.34 It is perhaps no fluke that most of the markers that were replaced in 2012 mention Native Americans in some respect or another—although some may have been replaced merely for physical repairs. The text on Marker #69, regarding the Medicine Lodge Peace Treaties, and Marker #95, about the Kansa Tribe, both seem remarkably more open about colonial forces in the area and their abuses of Native Americans. The latter, for instance, has remarkably more critical text than other examples, not resisting the horrific effects that colonial presence in the state had upon native tribes:

Through contact with Europeans and Americans, the Kansa contracted foreign diseases that had a devastating effect on their population. In 1825 the Kansa were forced to agree to a treaty that reduced their land to 10 percent of its original size. Two years later the government established an agency to protect the interests of the United States 2.5 miles southeast of here. It was the goal of the government to change the Kansa into American farmers, stripping them of their traditional way of life. In 1846 the Kansa were again forced to move, this time to an even smaller reservation near Council Grove.35

The Medicine Lodge marker also makes a point of noting the abuses of colonial authority, even though it is in a more understated manner: “Some chiefs signed the treaties without popular support; others misunderstood the agreements and later renounced them. When the agreements failed, the government responded with force.”36 This is a welcome change, but as previous markers examined illustrate, this critical view is not taken in every instance, and structuring absences remain.

The worry that this exploration has been attempting to uncover is the problems inherent in what the markers do not say, even in their replacements, and how these structuring absences paint a picture of the state that is not fully fleshed out. Consistently, each marker is historically accurate, but some are historically incomplete, leaving out some detail that can drastically change the way the marker texts are interpreted. This problem is not limited to historical markers and can be seen in general relations between Native Americans and settlers: “The past (…) plays a critical role in the political sphere, as indigenous peoples mobilize that past in order to assert their presence in the present. Colonial and settler societies, on the other hand, often seem to be predicated on a kind of constructed amnesia.”37 This “constructed amnesia” may not be intentional on the part of the KHS, but the markers tend to show traces of the willful amnesia Americans are often subject to with regards to the abuse of Native Americans and their land. It is better to remember these moments, especially within the realm of roadside markers that attempt to define their surrounding area.

Historical markers, as stated before and illustrated throughout this piece, are contentious objects. While they are dissimilar from monuments that seem to glorify past atrocities such as the Confederate monuments that have become objects of intense debate, markers in their current state subtly help colonial renderings of history persist. Most opponents of Confederate monuments celebrate “the symbols of white supremacy” being torn down but note that it “is just the beginning of defeating that which plagues communities of color.”38 The Kansas Historical Marker program does not have the same intentions that proponents of preserving Confederate statues do. The markers do not seem to intentionally promote white colonial superiority; they only perpetuate the normative power that the constant hold of colonial authorization has had on the region. Regardless, it is the structuring absences of these markers that can unintentionally perpetuate narratives consistent with this white colonial superiority—doubtfully the goal of the KHS. Intentions aside, these innocuous markers can easily become insidious because of this normative power. Though admittedly few people probably take the time to read them, as someone who does read them and appreciates the program at its core, these structuring absences are troubling features that do not affect each and every marker, but greatly cheapen those markers that are affected. Kansas is likely not the worst offender in perpetuating colonial superiority via historical markers, but it is the one I am most familiar with. It is important that Kansas not fall deeper into this trap, as Derek H. Alderman notes that states from the Deep South have. These faults in historical markers exist largely because historical markers and monuments tend “to conform to the United States’ tradition of narrating the past in consensual rather than critical terms, thus failing to engage in deeper critiques of racism, inequality and civil rights.”39 This dichotomy of consensual/critical is where most of the troubles lies. If Kansas were somehow able to work up the funds to rewrite the markers that need to have a more critical view of history—and the KHS seems open to this change—it could avoid defining space in strictly colonialist terms that continually assert the normalization of the white majority narrative in the sunflower state.

To reassert Augé’s claims: “There is no room there for history unless it has been transformed into an element of spectacle, usually in allusive texts.”40 There is perhaps scarcely a better example of these “allusive texts” imposing history on a non-place than these roadside highway markers, for it is also true that “what reigns there is actuality, the urgency of the present moment.”41 Historical markers display this urgency through a quick, clean version of historicizing the region. They are not meant to impede modernity, as that would be impeding mobility—interrupting the flow of the automobile non-place. They are meant to be “places of memory,” as any non-place is, but these memories are somehow devoid of any deeper, critical meaning. Instead, they assert modernity as acceptable, desirable, and, at times, unavoidable. The markers are only rarely critical of the nature of colonial conquest in Kansas or at a national level. All is not lost, however: “Place and non-place are rather like opposed polarities: the first is never completely erased, the second never totally completed; they are like palimpsests on which the scrambled game of identity and relations is ceaselessly rewritten.”42 Perhaps, if the structuring absences that mar this otherwise brilliant program were eliminated, the porous line between place and non-place could elevate these markers to true places, with history that need not resort to spectacle as they get closer to the full truth of historical events. Augé says on the concept of non-place: “It never exists in pure form; places reconstitute themselves in it; relations are restored and resumed in it.”43 Perhaps the historical markers are the catalyst to restore and resume these relations. If so, maybe they could be a small step toward serving a nobler purpose, even if the markers are just defining small patches of land on the side of a Kansas highway.

Thank you for reading Getting Spooked. If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, consider becoming a regular subscriber to get posts sent to your inbox. Become a paid subscriber to read dozens of archived posts, listen to members-only podcast episodes, or ask questions to be answered in Q&As. It is the best way to directly support the continuation of this publication. I also started a referral program that rewards archive access to those who share the newsletter with others, so be sure to tell any friends who might find this work interesting. The leaderboard tab is public if you want the bragging rights of your referral numbers.

Thanks to The Anomalist for linking to Pt. 8 of the Chris Bledsoe series. Be sure to check out the recent guest article from Reid on Puharich space kid Belita Adair if you missed it. Email me at gettingspooked@protonmail.com with any questions, comments, recommendations, leads, or paranormal stories. You can find me on Twitter at @TannerFBoyle1, on Bluesky at @tannerfboyle.bsky.social, or on Instagram at @gettingspooked. Until next time, stay spooked.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society, https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #59.

Augé, Marc. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London and New York: Verso, 1992. Page 77-78.

Ibid., page 78.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society, https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #97.

Utley, Robert M. Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984. Page 412-413.

Romero, Simon. “Latinos Were Lynched in West. Descendants Want It Known.” The New York Times. 3 March 2019. Page A15. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/us/porvenir-massacre-texas-mexicans.html.

Ibid.

Alderman, Derek H. “’History by the Spoonful’ in North Carolina: The Textual Politics of State Highway Historical Markers” Southeastern Geographer, Vol. 52, No. 4. Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press, Winter 2012. p. 356.

Gibbens, V.E. and G. Raymond Gaeddert. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 4. Topeka: Kansas Historical Society, November 1941. pp. 339.

Chinn, Jennie to Dennis Hodgins and Patrick Hurley. “re: Historical Highway Markers.” Kansas State Historical Society. 24 February 2010. Email record.

Augé, Marc. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London and New York: Verso, 1992. Page 101.

Ibid., page 96.

Pesses, Michael W. “Road less traveled: race and American automobility.” Mobilities, Vol. 12, No. 5. London: Routledge, 2017. p. 680.

Augé, Marc. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London and New York: Verso, 1992. Page 103.

Blackmar, Frank W. Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc. Chicago: Standard Publishing Company, 1912. Page 13.

Dyer, Richard. The Matter of Images: Essays on Representation. London and New York: Routledge, 1993. Page 83.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #60.

Turner, Alvin O. “Cherokee Outlet Opening.” Cherokee Outlet Opening | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH021.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #114.

Blackmar, Frank W. Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc. Chicago: Standard Publishing Company, 1912. Page 450-451. (At a tour in the Kansas State Capitol building when I was a child, this misinterpretation was rather fancifully assigned to the possibility that the Indian guide was referring to the rolling hills of “gold”—the tallgrass prairies that made up most of the state’s landscape. There was no mention of the guide being slaughtered for misleading Coronado in this tour.)

Another marker covering historical events from the same party of Spaniards, “Father Juan de Padilla & Quivira”, was replaced by a marker about one of Kansas’ most famous locals, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Father Padilla, the purported first Christian martyr in the Americas, no longer has a marker about his attempts to convert the Native American population. He lives on, however, in the first section of Kansas’ (the prog rock band) 1976 track “Magnum Opus” which is entitled “Father Padilla Meets the Perfect Gnat”.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #78.

Montgomery, F.C. “United States Surveyors Massacred by Indians: Lone Tree, Meade County, 1874.” Kansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 3. Topeka: Kansas Historical Society, May 1932. pp. 268.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #117.

Ibid., marker #112.

A mural representing the famous court case is now featured outside of the state supreme court building (https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-state-capitol-online-tour-brown-v-board-mural/20230).

Heitz, Lisa Hefner. Haunted Kansas: Ghost Stories and Other Eerie Tales. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1997. Page 102-109.

Ibid., page 107.

Ibid., page 191.

O’Brien, Claire. “’With One Mighty Pull’: Interracial Town Boosting in Nicodemus, Kansas.” Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring 1996), pp. 124, 118.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #42.

The railroad companies did indeed seem to intentionally evade Nicodemus, opting to create a rival town after numerous instances where a railstop seemed certain. From Chu and Shaw’s Going Home to Nicodemus:

Missouri Pacific officials made it known that the choice of routes would depend on the people who lived on the right of way. What they really were asking for was a public subsidy to help pay for the cost of construction—somewhat in the way local governments today offer tax breaks to attract industry to their areas.

How much did the railroad want? The Missouri Pacific wanted $132,000 for the Graham County stretch. Eight towns along the route would give varying amounts, with Nicodemus's share coming to $16,000.

In the spring of 1887, the citizens of Nicodemus voted 92 to 3 to borrow the money by issuing bonds. And when the railroad's surveyors arrived a couple of months later, everyone thought that a Nicodemus rail line was a sure thing.

They were wrong. The Missouri Pacific's track building stalled at Stockton, then stopped.

There were other railroads—two, to be exact.

One was the Santa Fe which also sent surveyors to look Nicodemus over. But then the Santa Fe, too, backed out.

Now all of Nicodemus's hopes lay with the Union Pacific, which was laying tracks along the other side of the South Solomon River. But the other side of the river was where those tracks stayed. More galling still, a temporary rail camp six miles southwest of Nicodemus grew into a rival town called Bogue.

(Chu, Daniel and Bill Shaw. Going Home to Nicodemus: The Story of an African American Frontier Town and the Pioneers Who Settled It. Morristown: Silver Burdett Press, 1994. Page 57.)

Chinn, Jennie to Dennis Hodgins and Patrick Hurley. “re: Historical Highway Markers.” Kansas State Historical Society. 24 February 2010. Email record.

While some tribal leaders agreed to textual changes, others “felt the markers were too negative” and “expressed (…) unhappiness with the project” in general. Other representatives worried that they “could not speak for the tribes” as a whole (Chinn). Eight out of ten tribes approved the rewrites, while the Cherokee Nation and Wichita & Affiliated Tribes either did not agree or did not respond to questions regarding the text. This may be specifically reflected in the structuring absences in the current text of the Cherokee Land Rush marker.

Mechem, Kirke. “Kansas Historical Markers.” Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-markers/14999. Marker #95.

Ibid., marker #69. (Like other historical markers, the details of this incident are the subject of debate. However, the Medicine Lodge marker represents the different sides of this divisive issue and the ultimate decision of the government to forcibly deny Native American sovereignty with a more critical lens than other markers. The use of the phrase “by force” has noticeably different rhetoric than other markers about interactions between Native Americans and colonial forces.)

Thrush, Coll. “Monument, Mobility, and Modernity; or, The Sachem of Southwark and Other Surprising Commemorations.” Ethnohistory, Vol. 61, No. 4. American Society for Ethnohistory, November 2014. p. 608.

Newkirk II, Vann R. “Growing Up in the Shadow of the Confederacy” The Atlantic, 22 August 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/08/growing-up-in-the-shadow-of-the-confederacy/537501/.

Alderman, Derek H. “’History by the Spoonful’ in North Carolina: The Textual Politics of State Highway Historical Markers” Southeastern Geographer, Vol. 52, No. 4. Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press, Winter 2012. p. 356.

Augé, Marc. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London and New York: Verso, 1992. Page 103-104.

Ibid., page 104.

Ibid., page 79.

Ibid., page 78.